Bach to the Future

Humankind's one indisputable genius. Don't argue.

I threatened ages ago to write a post on Bach, and hadn’t yet for two reasons.

The first is diffidence around implying I have the slightest expertise in the subject (which I most certainly don’t). The second is I kept thinking “Ooh, I must include that” and “Well, I have to recommend this, obviously”… and it got to the point where it was verging on being a well-meaning idiot’s guide to everything the guy ever wrote… which would have tried the patience of even the most forbearing of you.

One of the great things about liking Bach is there’s a literal fuck-ton of it, and it’s all good. The Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV) — the official tally of his output — lists well over a thousand works. It’s like the guy never slept. Part of that comes through him spending long stints as Kapellmeister or Cantor in places like Leipzig, where his job was to pump out new tunes on a near-weekly basis — like a musical pulp writer — but the guy also simply seemed to have endless glory coming out of his fingers.

So I’m just going to put up a few favorites amongst the well-known work, with a little background, in case you’ve even been Bach-curious but unsure where to start. You could make a decent argument that each one is the most beautiful piece of music ever written. You may even want to read the words first and then portion the music out, one a day or something — there are seven pieces here, enough for a whole week — to listen to with your eyes shut or while gazing peacefully of the window.

I’m not religious, but I do believe this: Bach is as close to God as we’ll ever get.

Sheep May Safely Graze

Some of Bach’s compositions that are commonly presented on a solo instrument were originally written as music for choir and orchestra. This is one such. The original cantata — “Schafe können sicher weiden”, the ninth movement of the Hunting Cantata — is beautiful. But the classic Petri transcription for solo piano is etherial.

The Solo Violin Sonatas — The Chaconne

This is a strong contender for the most extraordinary piece of music ever written for a solo instrument. Listen to it. This is just one person, on a thing with just four strings. It’s the final movement of Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004, and in essence comprises of a theme stated twice, on those two occasions followed by thirty variations, each of them precisely four bars long and starting on the tonic D minor and ending on the dominant A chord. But that’s not what you hear.

There’s a school of thought which claims these sonatas were composed at least partly in reaction to the death of Bach’s first wife, Maria. There’s a lot of contention over this, however, with some arguing that though Bach chose the title “Sei Solo” for the pieces (“You are alone”) there’s no record of him explicitly stating they were in memory of her, and pointing out that he remarried not long after (ignoring the fact this was a lot more common in days of yore, especially if there were kids that needed looking after). It could also refer to Jesus, or the fact it was composed for a solo instrument.

My position is that if you can’t hear loss in this, your ears aren’t working.

Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring

Again, a solo piano rendering of a cantata — “Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben”. The gold standard is Myra Hess’s transcription, which makes it sound do-able but is actually notoriously hard to play on account of the difficulty in weighting the melodic lines against each other, each hand often effectively playing two voices at once.

There’s a lot of options for a live recording — it’s one of those pieces that high level concert pianists tend to bring out as an encore — but I don’t think I’ve heard it done better than this from Trifonov (the audio is low, you’ll need to turn it up).

And seriously: if you ever feel that the world is simply too much, and you can’t deal with it, then put a cat on your lap and listen to this and you may well find that everything’s okay after all. At least for now.

Adagio from Solo Violin Sonata No. 1

My go-to for the Solo Violin Sonatas has long been Itzhak Perlman’s classic studio recording — but this live performance by the wonderful Hillary Hahn is simply outstanding. There’s a point about halfway through this video where they cut to one of the listening orchestra musicians, a gentleman resting his cheek on his violin, and I swear you can hear him thinking: “I’m never going to be as good as that, am I.”

This is how the Sonatas kick off, and I refer you to my above comments about the loss of Bach’s wife. Case closed. And I don’t even really care if I’m right.

Sonatas for Solo Cello

The first piece of music I ever learned on the piano at the age of nine was Bach (the first Prelude from the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier) but Tortelier playing the Cello Sonatas was my gateway drug into Bach in a broader sense.

I can’t on YouTube find the recording that I have, but this is close. I spent nearly forever one summer as a teenager trying to transcribe this (badly) for electric guitar, because I was a terrible nerd and didn’t have a girlfriend.

The Goldberg Variations

Now this, you likely will have encountered. The aria, at least. Amongst the many times it’s been used is in Hannibal (the Anthony Hopkins movie, not the TV show).

It’s impossible to talk about the Goldbergs without referencing Glenn Gould’s landmark recordings of 1955 and 1981. Gould went on to become probably the most celebrated classical pianist in history, but in 1955 he was a plucky 22-year-old hopeful. He came out swinging, too, not only choosing to render the Goldbergs on the piano (they were written for a two-manual harpsichord, creating very challenging hand overlaps when played on a single keyboard) but deploying quite different tonalities and speeds than had been heard before.

The differences between the two recordings are fascinating. The 1955 was one of Gould’s earliest, the 1981 took place only a few months before his death — and I’ve seen it alleged that part of the reason for the difference was that Gould’s beloved Steinway D concert grand had been damaged in transit, and repaired, forcing or encouraging him to reconsider his playing on an instrument that responded very slightly differently. That may be the case, but it seems more likely the change is simply that of a more mature musician tackling the piece in a different way. The older we get, the less obsessing over the details matters. It’s the story that counts.

The simplest way of describing the change is “he played it more slowly”, but there’s a lot more to it than that, and in this case slower does not equal easier, because maintaining the dynamics between the voices is actually much harder that way.

From the video of the later recording you’ll notice Gould’s famously idiosyncratic playing position, in which he sat far lower than most pianists: a function of the fact that throughout his performing career he used a chair his father had made for him as a child, shipping it from country to country. Another of Gould’s notable idiosyncrasies was humming along with what he was playing: despite the engineers’ best efforts, you can hear this from time to time in the 1981 version.

If you look under the hood of the Goldbergs you start to get an inkling of why Bach’s music so often feels like listening to some crystalline structure singing to itself. A serious deep-dive into the variations can be found here. There’s also a fascinating (and much shorter) look into some of the underpinning theory of Bach’s work (including his affection for the number 14, as it had numerological relevance to his name) here. Here’s a cool visualization of the workings of the 14 (see?) canons he later added to the Goldbergs (as puzzles, not even writing them out in full), and then there’s the utter madness of his “Crab Canon” from the Musical Offering BWV 1079 — where he composed a melody that could then be played backwards, on top of itself, and still adhere to the rules of counterpoint. I mean, that’s not normal. It would absolutely not surprise me if someone eventually discovers that Bach once encoded the entire sequence for human DNA into a sonata for bassoon, when played sideways, just for kicks.

You don’t know or care about all this while listening, of course. You just hear beauty. And there are many other fabulous recordings to explore — Gould effectively established the Goldbergs as the piece any Bach pianist needs to record in order to be taken seriously — including Angela Hewitt’s.

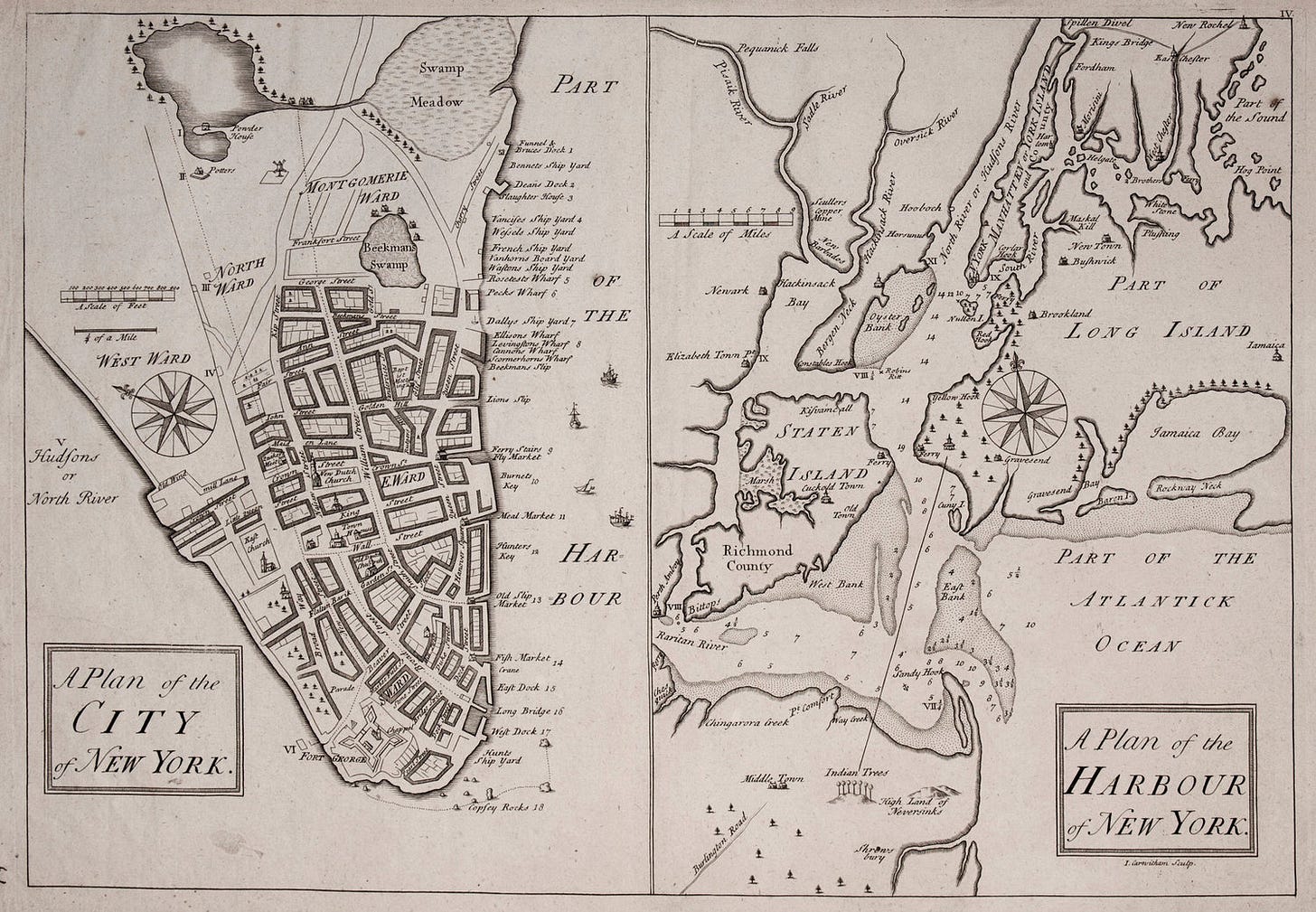

As an irrelevant sidebar, I’m often struck by how hard it is to connect history sideways, especially when considering the “Old World” vs things that appear to represent “modernity”. When you consider Bach, you may — as I sometimes do — think of him as being from fricking ages ago, I mean, like, nearly medieval, all weird wigs and being-in-oil-paintings and shit. In fact, when the Goldbergs were composed, New York State had a population of about 100,000 people and NYC looked like this:

Anyhoo.

The Brandenburg Concertos

Because the other choices are a bit intense, I’ll end on one that’s a little more jolly.

Now one of Bach’s most famous compositions, the Brandenburgs had a rocky early history — and almost never came to light. In 1721, in hopes of an appointment, Bach collected six pieces he’d written over the previous decade (copying out the music himself, as he didn’t trust a copyist for this particular task) and presented them to Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt. Because the then King of Prussia wasn’t big on patronizing the arts, Ludwig didn’t have even the relatively small number of musicians required to perform the concertos (the scoring is quite innovative, tailored for the exactly seventeen musicians Bach had at his disposal at his current gig), so the Margrave basically stuffed the gift in a drawer and forgot about it (and Bach).

When Ludwig died in 1734 the manuscript was rediscovered and sold for about thirty bucks in today’s money. It was then forgotten again, and only resurfaced from the Brandenburg archives over a century later in 1849, after which it was finally published and performed. The original manuscript continued to undergo a somewhat precarious path: during WWII it was being transported to Prussia for safekeeping when the train was bombed by planes — requiring the librarian entrusted with the pages to escape into the forest with them stuffed under his coat.

I don’t know where the manuscript is now. Probably hiding.

One of the most humbling experiences you can have as a musician is to play Bach. The contrast appears between the exquisite simplicity of note and line on the page, the thrill of knowing exactly what will happen next, the inevitability of each chord… and your fumbling ass-backward attempts to get the internal parts to sound any good while you plod along tonelessly wondering why you’re making this dreadful noise.

Bach is indeed as a deity. And. A lot of baroque music literally nauseates me. Yanno how music creates physical reaction? Ayup. And of course I don't KNOW if it's going to make me woozy until TOO LATE because who deprives themselves of magic no risk no reward etc.

I adore Glenn Gould. He did a little Toronto walkabout tour program that might still exist somewhere. I will never forget that a reviewer described him humming "like a demented bee". Another god amongst us.

Three weeks of tax season left light a candle.