A while back I wrote about the simple foods we cook that warm the heart better than anything else. This is about how certain foods, ones prepared by others, take us back.

We all know how music can pin a part of our minds and soul to eras in our lives. That song which zaps you to being an angsty teenager again, or an even angstier twenty-eight; the dumb summer hit of twenty years ago that somehow became “your song” before the protracted and soul-crushing breakup, and which you can never hear again without the kind of wistful, keening melancholy that nobody needs in the supermarket on a Wednesday afternoon; that tune your mother used to hum when pottering happily around in the kitchen.

I don’t think the visual arts can do this, or even writing. Yes, you may associate certain paintings or TV shows or books with a period in your life, but they don’t transport you back. Food can truly do this, however — almost as if hearing and taste are the most vital and visceral of senses. Which I guess makes sense: babies rely upon hearing and taste before they can focus their vision, and language takes years to acquire; whereas the ability to hear predators in the night and figure out by taste whether a piece of meat is safe both have clear evolutionary advantages.

When the food memory hits, it’s deep. When we lived in Australia for a year when I was seven, I took parentally-prepared lunches in to school four days out of five. On the fifth day I was given the treat of a small amount of money to buy whatever I wanted from the refectory instead. So I purchased something wholesome (I’ve no idea what) but always augmented it with a crunchy nut bar they sold. It was a blatantly artificial translucent lilac color and apart from the nuts was 80% sugar and 20% the kind of chemicals that are now banned under international treaties (this was back in the 1970s, when kids were allowed to drink weedkiller if it was cheap and they liked it).

I’d entirely forgotten this until one day fifty years later when wandering around a produce market at Moss Landing, twenty miles south of where we now live in California. I spotted a bar of what I suddenly remembered to be the same color, bought it, tried it. And was for several moments transfixed, motionless, no longer in the here and now. I was seven again. The four decades in between were irrelevant, meaningless. Time ceased to have bearing — in a way that even music can’t achieve — as if this bite was a literal continuation of one I’d taken when I was seven.

Which brings me to samosas.

It’s no secret that if you take meat and/or vegetables, season or spice them and wrap the result in pastry which is either fried or baked or boiled, you’re onto a winner. Seems like every culture in the world has latched onto this, from empanadas to bolani to pierogi to potstickers and gyoza to the stalwart Cornish Pasty, every single one of which I am happy to stuff in my face in quantities that might seem ill-judged. This is good eating, whatever the filling, method of preparation, or culture from which it derives.

My absolute favorite, however, a foodstuff in the face of which I am powerless, is a samosa. Any samosa. Vegetable, lamb, chicken. The fancy little crisp ones you get in expensive Indian restaurants, but also (actually by preference) the cheap, floppy, greasy ones you buy in corner stores — not least because I can take them home and microwave them before dipping them in HP Sauce. (Yes, I know, but I realized recently that as tamarind is a defining component of the sauce, this actually makes perfect sense. So there).

Samosas don’t transport me back in the way that virulently-colored nut bar did, but only because I’ve been eating them throughout my life, continually, voraciously, with a focus and dedication that other people waste on trivialities like “work” or “fitness”. Their role in my life does however come from a specific time and set of memories.

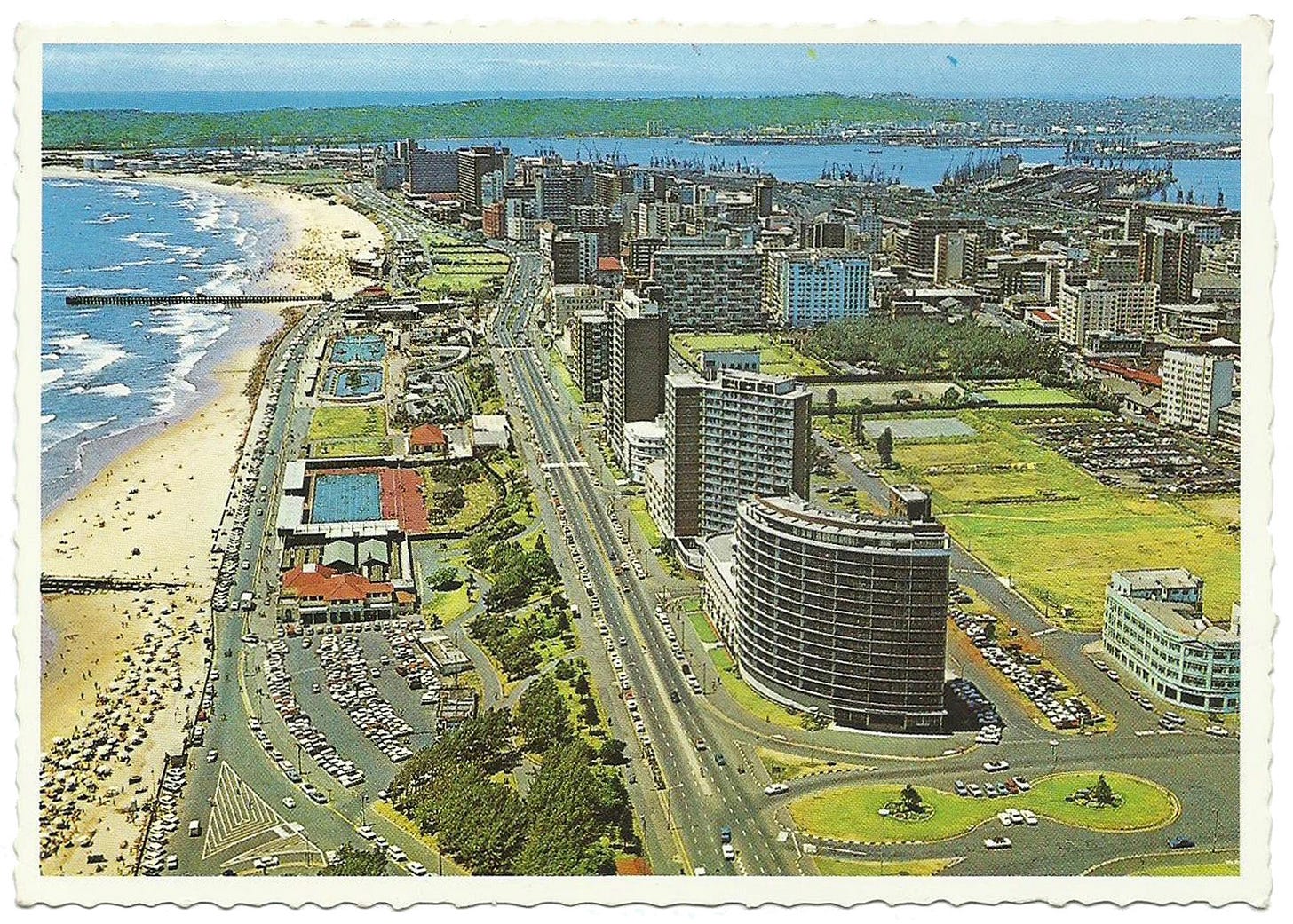

Before we lived in Australia we spent a year in South Africa. Much of this was in Johannesburg, the rest in the seaside town of Durban. My father taught at both the two universities nearby, which was unusual at the time as they were racially-divided. As his later work on Apartheid demonstrated, Dad wasn’t there for any of that crap — and this extended into the world outside academia.

The beach at Durban was also firmly segregated. There was a stretch of sand for whites, a portion for blacks or coloreds (as they were then called) and a third for the Indian population: the area has a long history of South Asian immigration (and fantastic food as a result: when my parents returned there in later years my mother would always bring back jars of hardcore spices). The divisions were clearly marked. At the end of an afternoon on the beach, however, my father would walk my sister and I out of the whites-only section and into the others, often chatting to random people he met along the way. He’d finish by taking us to a stall in the Indian section where you could buy samosas, and we’d stand and eat them there and then.

Those were my ur-samoas, under that bright South African sun of half a century ago, and this experience is doubtless present in some realm beyond words or conscious recall, the light in each bite I take of one now. Food isn’t just sustenance. It’s history. It’s character. It’s soul DNA… and I’m delighted to say that my son has joined with the tradition and now eats as many samosas as he can.

What about you? Do you have something like this, a food that shoves time aside and bundles the whole of your life up into one piece?

Let us know in the comments, please.

I didn't discover samosas until a little later, early 80s.

Before that, my food of choice, always late nights after a gig in or near Bradford, was the very basic curry that you used to be able to buy for a pound, including three free chapattis; they didn't sell rice, no-one did back then. It very much hurts me that these days they want up to two quid each for a simple piece of flat bread.

Keema Madras was, & still is if I can ever find a decent one, my single favourite food. Basic, tongue-numbingly hot. No airs, no graces. Food of the gods. For some reason if you ask for one in London you generally just get blank stares. I once got "Oooh, that could be interesting" & they had a go. It was close but no cigar. You also have to specifically ask for it hotter than they would normally do it. Curries have got much milder over the years.

This would be supplemented, for an extra 50p, with a shami kebab; not the soft squishy type subtly dipped in egg, these were a more heavy industrial version, a bit like a deep-fried burger. Served on large slices of raw onion & a splash of 'mint sauce' [thin yoghurt with supermarket jarred mint sauce, as in the stuff you put on lamb for Sunday dinner, with a dash of generic curry powder & cayenne.]

Complete the image with a brightly-lit, white-painted cafe, formica tables & a young lad, fourteen or so, who ran the whole front of house; taking the orders from a raised booth in the corner so he looked as tall as everyone else when behind the counter - a bit like Danny DeVito in Taxi - then dashing round, spinning plain white pyrex dishes towards you at some speed over the shiny formica surface, without spilling a drop. Food was served as it was ready, not when you wanted it, so your main would always show up halfway through your shami starter, crowding the table to bursting. Dig in, lads.

Cutlery was, of course, your three chappatis. They had one spoon behind the counter which would be ceremoniously presented, to peals of laughter, should anyone be foolish enough to ask for cutlery.

As a truly complete memory, it's hard to recreate. I can make the Keema Madras myself these days. It's also close but no cigar. I can make my own chappatis, again imperfect. The shami kebabs, I've not a clue how they did it.

I can, though, nail the mint sauce.

I lived in Cape Town for over a decade and have been back in California now for about the same. I was literally telling my husband today how sad it makes me sometimes that I can't just pick up some cheap samosas at every shop. Also discovered your books at the Cape Town public library so it was a great place to live for lots of reasons.