When we first moved to Santa Cruz from London we rented over on what’s known as the East Side of town, south of the harbor. This was formerly a separate unincorporated community called Live Oak, and many in town still refer to the neighborhood that way. Originally much of it was tulip fields, complete with a small and I assume ornamental windmill, now a low-key coffee and sandwich shop.

The area has a more relaxed and seasidey feel than the rest of Santa Cruz. We found a vacation rental on 14th — a mere block from Twin Lakes beach and also conveniently close to a very good taqueria — and negotiated to stay in it for eight months during the off season. Of course when I say “we” you should understand that I mean my wife, who took point on that and so many other things in those early days. And she does that now too. I sometimes think that if it weren’t for her, I’d be living in a box.

The house had two stories. We rented the upper, together with a small but airy semi-attic bedroom, which became my work space. The house was built by a man with a ship-building background. That showed. It was relentlessly but charmingly wood-paneled throughout, from the living room to the kitchen and even the large but curiously-shaped bathroom — which included a rock-lined open shower. For some reason (I suspect the guy constructed the house in an ad-hoc and unplanned way, and so probably just didn’t think it through) there was no window in the bathroom. As a result it was pretty dark but if you lit a few candles there was a definite vibe.

The high point of the entire structure was our bedroom, where the paneling was painted white and rose to a high and pointed ceiling. It truly did feel like going to sleep on a boat. Most of the living space was surrounded by decks, with Live Oaks — for which the area was named, obviously — pressing close, enabling a truly extraordinary array of squirrels to gambol in and out of our lives.

It was pretty great.

The ground-level space was a long-term rental with occupants who’d been there a while. Our neighbors for that year, Liz and John.

I know more of John’s story than of Liz’s because, during the times we’ve spent together — we catch up with them once in a while, though it’s now ten years since we’ve moved to the West Side — the bulk of the conversation has tended to split on gender lines, as it so often does. Not all the time, they’re a couple we like as a couple (I love it when that happens, it’s rare), and the chat is free-flowing and intermingled. And we don’t agree all the time. John and Liz are Santa Cruz radical liberals of the old school. My wife and I are half a generation younger and British and thus more Gen X and pragmatic, or else ideologically lazy. Either way, for whatever reason, I’ve wound up knowing a little more about John.

He’s a Santa Cruz native. His parents were too. Liz comes from slightly further afield, forty miles away down in Monterey. Despite this birth proximity they met in Paris, of all places. Liz was on a micro-budget camping expedition in Europe with two college friends. John had been in France for four months after leaving art school up in San Mateo. Upping sticks to Europe was a romantic gesture intended to give him space and inspiration to further develop his style (oil paint abstracts) and he’d already begun to suspect it had been a bad idea. While he liked the French, the feeling didn’t seem to be mutual (though, as we agreed one night, Parisians are whole type of French and often don’t seem to even like other French people very much). He found intermittent work waiting tables at tourist-orientated cafes where speaking English was a plus, and did a little busking, but money quickly got tight.

It had gotten to the point where he was sleeping in the Bois de Boulogne camp site. I’ve stayed there myself, thankfully briefly, and though picturesquely situated on the banks of the Seine it’s way sketchy, prostitutes plying brisk trade along the roads that criss-cross the center. John was there a decade before me and it sounds like it was quite a scene. One cold and rainy night he heard a commotion from the next tent and emerged to discover three American girls hectically shouting at something. It turned out to be a river rat which had made its way into their tent. Seine river rats… I encountered one myself on my trip and they’re a serious business. In low light you could mistake one for a small dog, assuming said dog had very short legs and scuttled around in a disconcerting manner, stealing anything edible. John helped the girls shoo the thing out, after which it transpired they had a couple bottles of cheap wine. They suggested sharing one of these in thanks for his intervention, the evening waxed convivial, and when Liz returned to California ten days later, John came home with her.

Liz soon started work as a teacher at a middle school in Santa Cruz and John wound up following her into that, too — in his case teaching art. He kept diligently painting in his spare time, sometimes selling canvases at one of the little stores spread throughout the repurposed Cooper House on Pacific Avenue (this was before the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, which took out the Cooper House along with significant other buildings like the St George Hotel, destroying the cheerfully ramshackle and counter-cultural atmosphere of downtown forever). Liz meanwhile taught history to grades six through eight, becoming increasingly frustrated with how little of the material related to the great wide world outside America’s borders. They married, and moved into a small house on the lower West Side back when that was something a person who hadn’t made a pile of money via a generic tech start-up could do. Many of those smaller wooden houses are gone now, including John and Liz’s first family home, replaced by bland Modernism and glass.

They didn’t find it easy to get Liz pregnant but eventually succeeded, a process sufficiently physically imperiling for her that they decided one child would have to be enough. When Joshua was ready to go to school Liz made a long-plotted career swerve and trained as an acupuncturist, soon afterwards starting a practice at the (newly-founded) Nine Leaves Clinic in Midtown. John continued to work at San Natana Middle School though by then he barely painted himself any more. What had once seemed raw and essential now rarely inspired enthusiasm, or in fact any emotion at all. He is open about his periodic struggles with mental health, and acknowledges that the several years after Joshua’s birth were a foreshadowing of what was to come.

Meanwhile Liz was going from strength to strength, volunteering at Joshua’s school and also helping to set up a community farm and garden project in aid of the local (and growing) homeless population. But then on March 4th 2003, she received a call at work from the Santa Cruz Police Department. Her husband had been found, in his car, half-submerged in shallow waters below a stretch of Highway 1 a mile south of Davenport (the tiny town that’s the next place up the road from Santa Cruz).

Miraculously, despite a dozen-foot vertical descent, his only injuries were cuts and bruises. Though he’d spent the previous hour in the Davenport Roadhouse bar, the police determined that he wasn’t above the legal limit for driving. Which of course raises the question of how, or why, he’d driven off a road he’d traveled up and down countless times. When he told us about the incident — this was back during the year we lived above them — he paused at this point, as if expecting to be asked that very question. Neither Paula nor I asked it. I’d noticed Liz covertly squeeze John’s hand a few moments before, as if in reassurance. She told me on a later occasion that two days after the accident she’d taken some trash out back and discovered all of John’s brushes and paints neatly tied in a plastic bag, waiting for the refuse truck. He’d put them there before his car left the road south of Davenport.

He left his job at the school and the next year was tough. What saved him, he frankly admits, was that after vaguely fretting about a mole on her neck for too many months Liz was diagnosed with a melanoma. It was small but those things can get tricky fast. This one did. John describes the time as an overdue wake-up call, something that finally cut through the fog. He supported her through the medical process and its aftermath, meanwhile taking on more of the household duties — something he’d previously been lax at engaging with.

He kept this up when they emerged the other side, taking on a year of homeschooling for Joshua when their son developed social anxiety acute enough that he didn’t feel able to go to school. Thankfully this abated and Joshua graduated from Santa Cruz High and subsequently attended Cabrillo Community College. He’s presently working as a barista at Eleventh Hour downtown while becoming a talented photographer, producing moody portraits of local people — including his parents.

After Joshua left home they downsized to the rental in Live Oak, choosing that option on the grounds that they could just take off and live anywhere (though both have confided that they enjoy living here in Santa Cruz way too much and that lighting out for the territories seems less and less likely as the years go by). Liz’s acupuncture practice is small but well-established and she has as much work as she needs. She intends to retire, she told my wife, when she’s dead: and not a moment before.

John never returned to teaching but more than fills his time with bits of work here and there, including helping out at Rodini Farm’s produce stand at the downtown farmers’ market on Wednesday afternoons, also at the East Side one that takes place just around the corner from their place every Sunday morning. Sometimes he sits in with the local bluegrass/folk band that plays the market, keeping the beat on guitar in the back while another guy leads on the banjo and someone else sings and a young woman with red hair plays the fiddle and little kids dance in the sunshine.

When we last saw them for dinner at their place a few months ago, John diffidently gave me something as we left. A small painting. Honestly I have no idea what it’s of, but that’s because he works in abstracts, always did.

He’s painting again.

The thing is… none of that’s true.

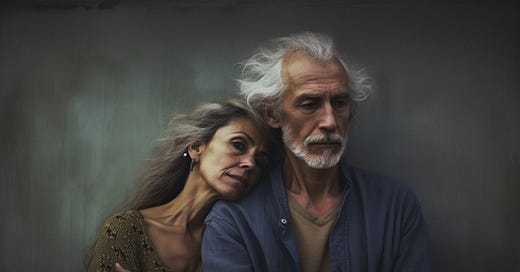

Well, the stuff about the house in Live Oak is, but John and Liz don’t exist. I did this piece as an experiment. I wondered: if I put up a picture — created by me in AI, using Midjourney, with a few tweaks afterwards in Photoshop — and wrote about two people, would a reader assume it was real life, and more so than if there was no “photograph”?

If so, does that make the writing creatively dishonest? And if yes, where’s the lie? And yes, I’m deliberately using my own job to push your ideas of what is acceptable in “making things up”.

I’m a fiction writer. My last two posts about Santa Cruz have been obviously “imaginative” (even if a few loons on Twitter bought a couple of them wholesale). If you buy a novel, you know it’s not going to be true… at least, you’ll be aware the events described didn’t happen, even if you hope it’ll be “true” on the level of evoking real life and the human condition. Of course if I wrote a work of fiction and said it was fact, that’d be a lie. But I didn’t say that. I presented a piece of prose, with a (fake) photograph. That’s all. I could have done the same thing with a stock photo of real people. Isn’t it in some way more “honest” to use a fake photo to talk about people who aren’t real?

So, yes, this is about AI again — because honestly that’s kind of the biggest story in town for creatives right now, and will be for some time. And there are firm and strident things to be said about the way in which AI systems take a liquid dump on idea of copyright, and people’s ownership of their own work (and style) — through scraping everything in the universe and incorporating that into its algorithms. Big Tech and the forces of capitalism have decided (as they always do) that the dictates of profit outweigh the rights of the individual.

The thing is — and I hate to say this, but I’m just being pragmatic — I fear that ship has sailed. AI exists, and people will make or save money because of it.

So it’s here to stay, and the question becomes how we respond. Part of that will involve figuring out what “art” even is.

Most art involves a contract between producer and consumer to pretend for at least a moment that the subject matter is real. AI takes that a step further by challenging assumptions of what is required for art itself to be “real”. Jean Baudrillard would have had a field day with all this. It increasingly seems to me that one of the biggest issues (in addition to intent, as I discussed in a previous piece) is that of implication.

I can make pictures using AI, not copying a particular person’s style but creating something unique out of a combination, like this set of four…

… which involves reference to two quite different artists (neither of whom produce work anything like this) plus a further generalized style (which neither of the other artists work in) and an additional reference to street signage. A unique combination, in other words.

I really like the results. And I could print them out, frame, and sell them. By doing so I’d be implying that I created them myself, right?

But… in fact, I did create them. Okay, I lifted the basics of the prompt from someone else and played around with it (there’s no honor amongst thieves, and the non-artists playing with AI will learn this: though also, don’t all writers and painters at least start by copying the people they like?), but without me, these images wouldn’t exist. The tool I used is somewhat immaterial. I remember “traditional” artists getting VERY uptight about digital painting when it arrived on the scene. Now it’s an accepted format with its own stars whose work is presented alongside people who, like John Radcliffe, use more old school methods like oils.

The thing is — and this is something else that AI-based creators are going to come up against very soon — at least traditional creators own their own tools, and their own skills. Yes, using AI does involve acquiring skills: my images now are way better than when I first started. But Midjourney recently brought out a version 5.1. It’s a lot better at some things, not as good at others as it used to be. Those prompts you used for the last few weeks to reliably produce a certain type of image? May not work any more. Someone took away your brushes. No, you can’t magic them back. You’re not in control of the machine.

And then factor in the idea of someone like Elon Musk buying your chosen AI, then insisting on stamping an indelible watermark on every image that comes out of it — and saying he now owns it. Copyright persists for the big guys, not you. Ya’ll are going to come up against the cutting knife of greed soon enough. Nothing’s free forever.

When talking about painting media, I forgot: John’s not real, though when writing about he and Liz they genuinely felt like they were. They would not exist unless I’d happened to create the picture at the top of the post while experimenting while putting together a deck, and it got my mind working, and presented their unreal lives to me.

I realize there’s a huge amount of oversimplification above. It’s such a huge subject that I’m neither able — nor wish — to try coming with a definitive answer. I guess my position for now is that AI (in the creative arena, its implications in other spheres is a whole different nightmare) is most practically viewed not as the death of the creative process, but the birth of new ones — and perhaps therefore a challenge to be grasped, played with, mastered.

It’s either that or give up and sit and complain, while the machines and their owners rise.

What do you think? Comments, please.

I have so many thoughts about AI and viewed through the lens of the current WGA strike, not many of of them are complimentary. I think AI has a place as a TOOL, much like digital painting devices are a TOOL for the imagination of the artist. But they are not a replacement for the artist. And that's what I fear AI will become or is becoming.

I wish I could say that AI will be a complementary tool. But there appears to be a wholesale push by AI tech bros to make the creative process more efficient and less error prone by removing the human element from the equation (and of course, to save companies money by not paying the human). There's a push to make creating art less tied to the complexity of humanity, when it's actually the time spent dreaming and the mistakes that are made that, in my humble opinion create the best art, whether that's paintings, photos, screenplays, novels etc.

This push to shove actual humans aside so that AI can create art instead of them should be ringing so many alarm bells. And the fact that the AMPTP refuse to agree to the WGA's condition that no AI should replace the writer at any stage of the process and instead they want to meet annually to 'discuss the technology' is a clear indicator of this intent.

Re: your beautiful account of Liz and John, you were inspired by the AI photo but your words are human. You are a human being. That's the difference.

No AI can make me feel how 'She told me on a later occasion that two days after the accident she’d taken some trash out back and discovered all of John’s brushes and paints neatly tied in a plastic bag, waiting for the refuse truck. He’d put them there before his car left the road south of Davenport' can make me feel.

Because even though an AI could technically write a sentence like this, it's not written through the lens of the human being. It doesn't have the unique world of experience that the specific human being who wrote it does. And for me, that's why I read; not just to enjoy an imaginative story, but to experience the filter through which the writer has written the story. That's a layer that AI can never ever replicate. And that's the layer which for me, is humanity. And art.

Thank you for this - I've seen a lot of what appear to be knee-jerk / denial takes on what is first and foremost a set of tools. Access to synthesisers haven't turned me into Depeche Mode; Google Maps didn't make me an explorer; Midjourney hasn't made me an artist. I don't write longform drafts in pencil, nor do I turn off spellcheck so I can flex my many hours of childhood solitude spent reading Readers Digest's 'It pays to enrich your word power' section and playing Boggle.

What I have done is had a lot of fun using AI as an idea reflector and explorer - my version of your story is this set of book and paper objects: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cq50crYodNk/ these only exist because I asked Midjourney what it thought a vintage alien stamp might look like, and a whole series of 'what if...' ideas flowed. I decided that to be on a stamp you should be 'important', and quickly followed he was an explorer of some kind, and had taken various Earthly forms (processed images from stamps to then generate a 'family'). I asked myself why he explored, and invented a religion, and a home planet, and added backstory in ChatGPT. I took some wrong turns. Some of what was generated was... mundane. But I printed various bits out and assembled them in a sort of 'cache' and now I have a story - a physical story - in a box. And I tell it often. Because the three hours or so it took to make the story were joyful, playful, and in a _mundane_ way turning this digital gubbins into paper seemed rather arty. Perhaps I am an artist, after all. What's the saying - 'any technology sufficiently evolved looks like magic?'

I understand why people are getting vexed about creativity and 'synthetic' reality. But as you say, it's here, deal with it. And we've dealt with many such transformations before. But your other point, about ownership and IP is the kicker. It is not AI I fear - not the tools, not the outcomes - it's the people behind the tools. The clever people, the egotists, the altruists, the opportunists. The capacity for unintentional harm is tremendous. There is the risk of concentration of power like we've never seen before. Instead of jumping up and down about sudowrite or byword or Dall-E 451 or whatever tool is launched that day, folks should be getting on to their politicians, and getting guardrails put round it.

Because it's all fun and games, until someone loses an eye....