Writing for TV

And three songs to put in your ears

This morning I happened across, in a notes app, a short list of observations about writing for television. Evidently I’d jotted them down for myself a while back and I thought I’d share in case they’re any help.

NOTE: These are pretty basic observations and I’m not claiming to be a source of wisdom on the subject, merely someone with a little experience, via both my own work and several years trying to help guide other writers through pitches. Far deeper and much smarter dives into writing for the TV industry (and an “industry” it is, and that’s the first point to internalize) can be found on Cole Haddon’s excellent 5am StoryTalk and Julian Simpson’s always-interesting Development Hell.

This is merely a list of ten simple things I think are worth knowing.

1.

A television pitch is not explaining to people what happens: it’s for telling the execs what it’s ABOUT. That operates on both a series-wide and per-episode basis. Don’t just tell them what occurs in the pilot: find the essence of the hour. Drill down to what the problem is, how the characters seek to resolve it, what we learn about them in the process, and what comes of their attempts — a crucial change in circumstance that’ll drive the show into the second episode, and its new problem, and then into the episodes beyond.

Your key job is communicating how a show will make the viewer FEEL — causing the exec to believe they won’t be merely watching something, but a wide-eyed part of it.

2.

That thing you’re working on for free because it’s a slam-dunk? It’ll never happen. Real producers pay. Same applies to guys (it’s seemingly always men) who claim they know how to game the system and are definitely going to finance a whole slate of low-budget movies by pulling in finance from Bruges and Azerbaijan. They won’t. If you’re not being paid, make sure you’re working on your own stuff. Sure-fire = horseshit.

I’ll caveat this rather bullish note by saying: well, kinda. The truth is we all work for free in hope of progress (I’m doing some right now, and asking others do the same). There are times when it’s unavoidable to get a show to the point where it’s pitchable. But just make sure it’s with people who have a clear route to actually making the thing, or who you can learn from, rather than randos who claims they can tap into vast reserves of shadowy private investment but whose IMDB page is curiously empty.

3.

Past the logline, the execs will not ultimately care a great deal about your fascinating ideas and they will not simply trust you to figure out the character stuff later because, duh, that’s what writing is. If you don’t make them care about the characters, then you could be selling the meaning of life and they still won’t buy it.

(The same is largely true of a show when it gets made. A small portion of the audience will be transported by your concept, and a larger one will care about the plot. But everybody will be investing in the people it happens to. People care about people. That’s just the way it is.)

In the pitch, this is not about describing how characters look or where they went to school or their favorite kind of coffee: it’s showing how they will drive the story. Who are they, how do they fail, how do they learn, and how will they change? What’s wrong in their lives, what do they want, and how will this story fix that? This is the stuff that audiences care about, and the execs in the room are your first trial audience.

4.

There’s no point hassling your reps in the hope of good news. If they’re not jumping on the phone to you, there’s no news — or it’s bad news, which they hate sharing.

Do some work instead.

5.

Execs always want to know “Why make this now?” and, annoyingly, the response “Because it’s obviously a great idea, you muppet” will not suffice. Trust me, I’ve tried. The question behind the question is: “Why is it not an insane idea to spend tens of millions of dollars making your show, in this goddamned market?”

Remember what their job is. If they like the pitch then next step is they will then have to try to sell your treasured been-working-on-it-for-months baby in two minutes to some faceless uber-exec you’ll never meet and who’s 99% concerned with the money. Give the exec the ammo to do that job — which boils down to providing them with maybe half a dozen sentences that sell the show, along with a feeling of enthusiasm.

Pitching is not about nuance: it’s about selling, and what you’re selling (to deploy the old advertising adage) is the sizzle, not the steak. Do not describe the protein structure of cooked beef. Show them a juicy slice of it being slapped on a grill, the flames, the sizzle… get them to feel they can literally smell it, and you might get a sale.

6.

Your reps will almost never get you work. They can, however, fight to stop you getting fucked over for the work you find for yourself.

This may sadly sometimes involve you losing the job, because the sole purpose of the studios’ Business Affairs departments is to make everybody angry and sad.

7.

Your most marketable characteristic isn’t being talented — got zillions of those guys and gals — it’s not being a pain in the ass. Be cheerful and responsive and hardworking and amenable (even when getting fired: what goes around comes around, and you’ll be remembered for not making their life hell — Julian has a great piece on this). Hitting deadlines helps too, so long as you don’t expect execs to reciprocate.

They’re in business, not art. You are too. So was Picasso. Have fun with it — not least because if you’re not comfortable to work with, you won’t get hired again.

8.

As a writer, remind yourself often that execs can’t do what you do. But then also remember that you probably can’t do what THEY do, either. There are some immensely sharp and talented development people out there, folks you can actually learn from both creatively and in terms of understanding their side of the business.

It’s a partnership — together, you may get shit done. Find the smart people you trust. Work with them. That’s how things happen.

9.

In the world of competitive barbecue — where judges walk around taking little tastes from what may be hundreds of hopeful teams — it’s common practice to make your food just a little hotter and sweeter than you would if someone was going to eat an entire plateful of it. You’ve only got that one hit to impress, so you need to turn it up a little. If you’re trying to pitch with a pilot, consider making that script a tiny bit faster, funnier and fuller than it might end up being when actually shot.

This is a private theory and metaphor, so it may be bollocks. But it makes sense to me.

10.

Ultimately, your only sure reward as a writer OR exec is to do things that — whether it gets made or not — you enjoyed working on, jobs where you can look back and feel good about what came out of it, or believe there was lasting value to the experience... even through just having had a good time for some of it. Fight the good fight.

The creative life is a process. There’s no finishing line.

If you have any thoughts, insights or questions, let me know in the comments…

And here’s the three songs I’ve been listening to most this last week…

All The Rowboats - Regina Spektor

She’s far from unsuccessful, but Regina Spektor still deserves to be much, much more widely known. From sweet-sounding but haunting songs like Samson to Eet to the anthemic Better, time after time she produces music that’s not only beautiful to listen to but often also delivers odd little oblique perspectives.

A good example is the one I’m listening to most at the moment: in which she imagines works of art as prisoners incarcerated in galleries and museums…

“Masterpieces/serving maximum sentences/it’s their own fault/for being timeless…”

And she’s got a great new album out too, so get on it.

Different Drum - Reagan Richards

There’s the original by Michael Nesmith, and the original (and excellent) cover by Linda Ronstadt and the Stone Poneys — but I marginally prefer this pretty similar version, which seems to land the killer last line the hardest.

Ich Will — Rammstein

I’ve long had a soft spot for Rammstein, despite the fact (or maybe because) they come on like the state-sanctioned house band of some nightmarish dystopian future. Providing a live version of this classic track, because these guys do a show.

There’s an earlier version here — in which they look even more like everything that everyone always warned you about. If you like Ich Will, check out the more recent and messianically nihilist Was Ich Liebe…

So many (more or less) universals there. I work in product management -- we have to sell features to the business, who sell them to others. TIL that a logline is a supercharged user story, and that has utility. Also the point about giving others the ammo they need to sell your stuff is something that should be metaphorically or literally beaten into people.

I think novelists could dot down some points from this as well. It's easy to forget that your art is essentially a product too that needs to be sold and marketable (at least if you want to succeed).

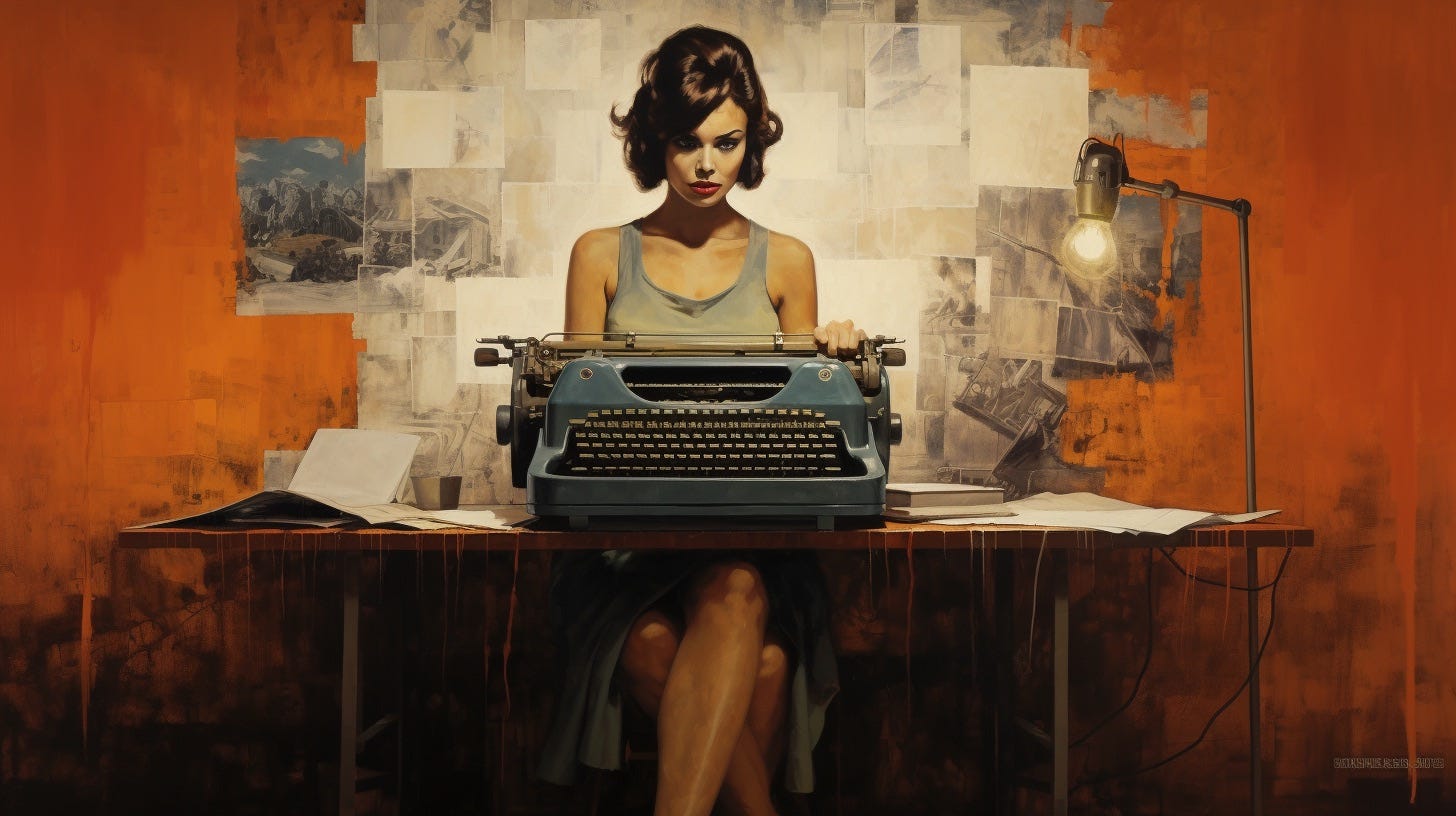

Having said that - can we talk about that picture in the middle? The one with the woman in front of the typewriter? It's enchanting. Is she inviting me to come jot down what she's saying? Is she the exec? Love that image.

Oh, and of course Rammstein! ;)