In Conversation: Tyler Jones

A chat with the most exciting new voice in horror fiction

A couple of years ago, out of the blue, a guy got in touch with me.

He had kind words to say about my fiction, and a tentative request: would I consider reading a novella he’d written, with a view to providing a quote? This happens from time to time and in all honesty, often I have to regretfully decline simply because I don’t have the bandwidth. This time, however, I said yes: and I’m very glad I did.

That novella was Criterium, and it only took about two pages for me to realize I was reading something that was both exceptional and unusual. It stayed that way. I was happy to blurb it and even more happy — when the request came — to consider writing an introduction for Tyler’s first collection, Burn The Plans.

My expectations for the collection were running pretty high, but still didn’t come close to hitting the mark. I read the book in somewhat difficult circumstances. My father had recently died and I was in the UK spending one of several two-week periods clearing out his house, the place in which I’d grown up. I was jet-lagged to fuck, physically and emotionally exhausted, and — of course — grieving pretty hard. Much of the book was read either on 40-minute tube journeys to or from my father’s house each day, or in my Soho AirBNB in the evening, surrounded by piles of childhood belongings that I had to triage for packing, or just throw away.

These are not the ideal circumstances in which to hope yourself to be transported from the here-and-now, and yet that’s what the stories did, each and every one — for which I will always be grateful. The stories are remarkably varied, but all are doorways, none leading quite where you expect. As I said in the introduction I eventually wrote: Burn The Plans is one of the very best collections I’ve ever read, and I feel no hesitation in placing it up in the realms of writers like Joe Hill or even Stephen King. It’s that good. That relentlessly, dependably, seriously, good.

Last week I read Tyler’s excellent new novel, Midas, and it struck me it’d be fun to have a chat with him and introduce you to his work. And here we are.

So, Tyler: Tell us a little about yourself: what made you start writing, how long you’ve been at it, what you’ve done so far...

TYLER: First of all, thanks a ton for the chance to chat about books, writing, life, and who knows, maybe I’ll even sneak in something about UFOs at some point.

I’ve been interested in storytelling for as long as I can remember. But there was a moment—I must have been 9 or 10—when I was watching Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade on VHS, and that name Spielberg stood out to me. Hadn’t I seen that name in Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., and the other two Indiana Jones movies? One guy made all these films?

That started an interest in the people making the art I connected with. Whether it was Mark Twain, C.S. Lewis, Stephen King, or Cormac McCarthy, from that moment on I followed artists more than anything. Picked books based on who wrote them, movies based on who directed them, albums based on who made them. I’m still that way. If an artist has earned my trust, I give it pretty blindly. And because of that, I’m a terrible critic. Oasis is my favorite band of all time, and I love even their worst album.

I’ve always been an avid reader, so there came a point when I wanted to tell stories, too. And like a dummy, I jumped straight to writing a novel. Which was terrible. So I wrote another, and that one was maybe a little less terrible. Then a third, and a fourth, and a fifth. Each time learning how to tell a story better, tighter. How to cut whole scenes that didn’t need to be there. I even wrote a 700 page behemoth that ended up being pretty awful…and so much longer than it needed to be.

I wrote novels because I figured that’s what writers did. I didn’t really read story collections at the time, and I’d heard the only way to get published was to get an agent, and the only way to get an agent was with a novel.

Eventually, I wrote a book I believed in and started querying agents. No luck with that one, so I wrote another that I believed in even more. While waiting for agent responses, I got antsy and wanted to put some work out into the world. I had a novella (which, as you know, are not always easy to get published) so I decided to put it out myself. And that novella was Criterium, which I actually asked you to blurb. I’d been a huge fan of your work for years and had just finished The Anomaly when I reached out. I had no idea how to go about it, so I just wrote a fan letter and asked if you’d be willing. To my shock and amazement, you were. Not only that, you gave such a wonderful and generous blurb that still makes me smile to this day. Since then, I’ve published numerous short stories in anthologies and magazines, along with several books including The Dark Side of the Room, Almost Ruth, and Burn the Plans.

The novel that I was querying eventually connected me with my amazing agent, Elizabeth Copps, and is now published in a beautiful, limited edition from Earthling Publications. That book was Midas.

MICHAEL: I’m interested by what you say about focusing down on particular creators and deep-diving, because I’ve never heard someone say that before — but I was exactly the same. With “horror” it was (of course) Stephen King, and Peter Straub, Ramsey Campbell, a few others — including contemporaries of mine like Nicholas Royle. I not only read everything they’d ever done, but then reread it, and reread again (much as I had with Kingsley Amis and Douglas Adams and Joan Didion before I got the horror bug). There were other writers like Clive Barker who I enjoyed, and knew I should read, but who didn’t drag me in as deeply.

When I later swerved more toward mystery and noir I added the three Jims: Jim Thompson, James Ellroy, and James Lee Burke. Again I followed that pattern of reading everything, usually more than once (I must have devoured Ellroy’s LA QUARTET series four times each) — as if to truly absorb and inhabit what they were doing by living within their prose universe. I didn’t feel I had to read every crime novel out there, or every horror book (though I was still religiously tucking into each King or Straub novel or collection that came out, immediately): it was the specific voice of some writers that attracted me, rather than the genre they were writing in.

I suspect it’s the same with a lot of people who become writers: they have an nascent voice inside and that’s the thing they most want to be able to express, but they intuitively accept and understand that it needs refining, developing, some serious gym work before it becomes their own — sometimes through aping or absorbing the work of others (much as art school sometimes involves copying the work of old masters, to both understand their work better and muscle-memory the techniques). It’s not so much a matter of wanting to sound like them, more a case of wanting to sound like yourself, and sensing that certain writers may be able to lead you part of the way there... until you’re confident enough to stop glancing back.

One of the most remarkable things about your writing is that — while presenting a unified voice and vision — you have the confidence to range all over the map when it comes to the subject and tone. When I read Burn The Plans, it struck me that the only time I could remember seeing as much variety within a single collection was Joe Hill’s Twentieth Century Ghosts, the last coming-from-nowhere collection that blew me away (and that was twenty years ago). Burn The Plans, like all of your writing, is resistant to categorization. It is what it is, and that’s all there is to it.

One of the frustrations of this, however, and of writing in general, is the industry isn’t really set up for writers of voice — but for those of genre. It’s right there in the way bookstores are arranged. There are a few novelists with the stature to write whatever the hell they like — Neil Gaiman, for example — but usually both publishers and readers are unsettled by writers switching apparent genre and prefer them to pick a lane and stick to it. The writers you cite as favorites don’t fit in any one box, which doesn’t surprise me: often the best writers draw inspiration from wildly-differing sources because what they’re listening to, and using to help sculpt their own voice, is something far deeper than superficial genre or subject — and instead some undercurrent of storytelling or perspective or feel.

Do you actually see yourself as a “horror” writer? If so, does it feel like it might become a constraint — or are you happy sitting there, at least for now? Do you feel it even matters?

TYLER: To your point about doing a deep dive into the oeuvre of certain writers, at first, it wasn’t a conscious decision. I did it with McCarthy, Don DeLillo, Paul Auster, Philip Roth, Dave Eggers, David Mitchell, Siri Hustvedt, Anne Rice. It was like a long mood, almost. Several months of my life would be spent in the stories, prose, mood, and language of one writer. It didn’t occur to me until much later that I was studying the work, rather than simply reading it.

I do that with music too. In fact, I just recently got into this band Silversun Pickups. I’ve been listening to all their albums on a loop since July. Obsessive? Maybe.

Thanks for the kind words about Burn the Plans, and to compare it to 20th Century Ghosts? Wow! Joe Hill is my favorite writer. I’ve read and reread his work more than any other writer. Something about his prose and storytelling hum at a frequency I really connect with.

Whenever I start writing, whether it’s a story, novella, or novel, I look for the voice of the thing and try my hardest to make it different than what I’ve done before. Like writing in a rural dialect (“Trigger”), or the broken/poetic English of an eastern European immigrant (“The Golden Rule”), or even a young child (“Boo!”), these aren’t meant to be gimmicks, but genuine attempts to tell the story as best as I can from the perspective of a certain character. Doing this also puts me on edge. A slight bit of discomfort isn’t necessarily a bad thing when writing, I think, because it means the story is as much a process of discovery for me as I hope it is for the reader.

In answer to your question about being a “horror” writer, I’m comfortable there…for now. But I also don’t see that changing any time soon. “Horror” is a somewhat tricky word because of how vast and varied the subgenres are. To one person it can mean a psycho with a chainsaw (blood, gore, shock etc.) and to someone else it could mean a ghost whispering in the walls. I find it interesting that one of our most famous and beloved Christmas tales is a ghost story. Dicken’s A Christmas Carol.

For now, at least, my stories will usually contain a dark, mysterious, and/or supernatural element, because that’s what I love to read, and it’s the kind of story I love to tell. I’ve never been scared by a book or a movie. I’ve been unsettled, sure. But never scared. So, writing to scare someone has never been my goal. I like creepy stories, unnerving tales, but most of all I love stories with relatable characters set against the backdrop of something strange. One of my favorite Stephen King books is From a Buick 8 because it’s so character driven. We never forget about the car in the shed, in fact, almost all the events revolve around it, but it’s such a deeply human story that I’m sucked right in every time I crack that book open.

Maybe the “constraints” are there only as much as we allow them to be. I grew up watching old movies from the 1940s and 50s, so my preference will always lean toward shadows, flickering lights, and transparent apparitions more than it will toward the in-your-face blood and gore.

I think the genre label is helpful for bookstores and libraries, but I’ve found readers to be very discerning. In my experience, a reader typically doesn’t like just one type of horror. They can, and do, read widely and appreciate all the variations.

MICHAEL: That’s so true about horror — it contains multitudes. I’ve never been drawn to gore, and actively detest the “torture porn” end of the field in movies like Saw and Hostel, but there’s so much other breadth in the genre. My early reading was “literary” and SF, and it’s possible I’d never have got into horror at all were it not for discovering Stephen King, probably the best practitioner (certainly the most successful) of one popular style of “horror fiction” — the kind born out of, and functionally all about... a fascination with humans, and their nature. People. What they’re like, their stories, how they interact, and why.

Often those are the best parts of King’s books, certainly the bedrock without which the spookier stuff wouldn’t have resonance. I’ve been known to re-read just the first half of some of his books, for the richness of the character material as he’s laying out the groundwork, then put the book aside before it devolves into a plot I wasn’t as engaged by: The Tommy-Knockers, for example, and especially Dreamcatcher — which utterly loses me in the second half but has brilliant stuff at the beginning.

It seems to me that horror is probably the genre where writers seem most interested in real people. The only book that’s ever scared me was Pet Sematary, and that wasn’t actually being “scared”... it was knowing what the character was going to do, and what a terrible idea it was... and yet understanding how it was emotionally unavoidable.

The other side of horror that really captures me is what I think of as “the uncanny”. Writers like Ramsey Campbell, MR James, Shirley Jackson... stories where something’s simply not quite right about the world, and the author has the confidence to let it sit there, gently vibrating in your mind, unsettling you. There’s been a lot of very good TV in that area recently too, especially from Europe — shows like the German Dark, French Les Revenants and the Belgian Hotel Beau Sejour. The Icelandic Katla was great, too — though lord, that was emotionally punishing.

Interesting to hear you’re seeking out challenges in terms of capturing specific voices, and the worldviews they enshrine. That’s one of the most important jobs of writing: to try to put yourself inside a character and deliver that specificity while at the same time yielding a universality which will make it accessible. A bit like acting: “Here’s a person: I’ll make you believe in them, and through that allow you to be viscerally affected by what’s happening in their lives.” And perhaps that’s why character is so important to horror writers. In SF often you’re trying to engage the mind, evoking a sense of wonder through ideas. Horror is generally about making the reader feel something in their heart and gut, and to achieve that, the characters have to feel real.

An over-simplification, perhaps. I’ve had a weird relationship with genre. I started off writing horror short fiction — as we both understand “horror” — under the name Michael Marshall Smith. Accidently wrote an SF novel, then two more (despite the fact that out of the hundred published shorts I’ve published, only two have been SF). Three serial killer books as Michael Marshall. Then side-stepped into supernatural thrillers under the same name. Then a more “adventure”-style thing with two novels as Michael Rutger. A couple of other experiments along the way. I’m really not great at picking a lane, but within that — like you — there’s always been an irresistible draw toward the dark, mysterious, uncanny. If a story doesn’t have those elements in there somewhere, however small (and sometimes the small weirdnesses are the most affecting) I simply won’t get out of bed to write it.

The big thing you’ve got out right now is Midas. One of the things I loved most about the novel is how distinctive it is, how hard to categorize, how confidently “of itself”. It’s about gold, and greed, and especially grief, and winds a story around those themes that stands to the side of any easily-identifiable genre. Without giving anything away, could you tell me a little about how the story came to you, and what you were most hoping to communicate through it? What was the kernel of darkness that made you know this was a story you had to write?

TYLER: Funny you mentioned Pet Sematary as a book that “scared” you because Midas was written in direct “conversation” with that novel. I saw the 1989 movie when I was young (maybe too young) and the feel of it stuck with me. I always been fascinated by the idea that one story can be in communication with another. Riffing off it in a way, like a one-sided conversation, or a debate, even.

Pet Sematary, as I recall of the novel, builds up to something we know (and dread) is coming. I wondered what that story might be like if the focus was shifted to grieving parents, and the cost of trying to get back what they lost wasn’t death but brokenness. Also, I wondered what Pet Sematary might be like with a villain, and a cult, and a endlessly growing house, and a talking wolf, and…

The kernel was actually simple: I saw a horse walking along a path on a foggy morning. I was with my wife and kids at a camp for families who have children with disabilities. This horse, Goliath, was powerful but patient, allowing children with all manner of physical and developmental disabilities to ride him up and down this trail. But this one morning in particular, I walked out to see him in his pen, mist drifting around his body so all I could see was this long, mournful face. And the image of a riderless horse coming out the woods popped into my head so clearly I had to run back to our cabin and write it down. That image eventually became the first chapter in Midas.

Who was the rider?

Who finds the horse?

The horse made a “western” setting inevitable, but I wanted to avoid all the standard tropes, which is why there are no swinging saloon doors, gunslinging sheriffs, or gruff strangers coming into town to clean things up. In a way, the story could almost be set in a medieval village and work just as well.

Not to get too depressing, but death was something I’d been thinking about a lot when I started this book. I tried to dig to the heart of what I was thinking and reading about. There were some personal things I was clearly trying to work through (clear to me now, anyway) but I couldn’t do it all in one book. I wrote another novel called Almost Ruth, dealing with similar themes, then another called Night of the Long Knives, and it wasn’t until I wrote a novella called Full Fathom Five, did I feel I’d finally exhausted my emotional connection to the subject.

So, yeah…death. How it clarifies being alive. How it’s the only certainty in this life, and yet it seems to be the one thing many of us avoid thinking about in any serious way. We all have to come to terms with it at some point. Which is something I love about fiction. It allows us to approach in the unknowable from different angles. To reach intellectual conclusions at an emotional level.

What’s interesting to me (though maybe not to anyone else) is the prose in Midas. I subconsciously wrote it in a minimalist sort of way, eschewing lushness for precision. Looking back, I think it was probably the nervousness of tackling so many things in one novel that I didn’t want the language to distract from the story. I wanted every sentence to be as clear as possible.

You used the word “uncanny” and that’s perfect. The feeling of, “something’s not quite right.” It’s hard feeling to describe, but impossible not to recognize when you feel it. It’s certainly something to aspire to when writing. Which is part of why I look for that in what I read, and strive for it in what I write. We already live “real life,” why would I want to read about it? Give me the things that can’t happen and use it to illuminate the real. The Uncanny becomes a sort of flashlight, doesn’t it? A narrow beam of light revealing pieces of something much bigger than we’d dared consider before.

And yes, Midas is available now in a deluxe, limited edition from Earthling Publications. As you know, Paul Miller (who runs Earthling) is a gentleman, a scholar, and a passionate publisher. I’ve been incredibly blessed to work with him on this story. From the hauntingly beautiful cover art by Vincent Chong (scratch working with him off my bucket list) to the humbling introduction by Josh Malerman, Paul has put together a stunning book I’m so proud to be part of. This limited edition is only 500 copies, but my agent and I are hopeful it’ll eventually find a good home for a wider release. Fingers crossed.

And…you might be interested to know that your novel The Anomaly was a direct influence on Midas. I’ve been a fan of the Michaels (Marshall Smith, Smith, and Rutger — which sounds like a law firm) for years. But that novel in particular lit me up in so many ways. Adventure, danger, mystery, legend, myth, and a twist on tropes that ventures into new territory.

I’ve recommended that book to so many people, and continue to do so.

Coincidence both of our novels contains mysteries within caves? Nope.

Speaking of your books, have you ever written a story or novel that you view as “in conversation” with another piece of work?

MICHAEL: Delighted to hear that The Anomaly was in the mix there — thank you for recommending it, and for the kind words!

Fascinating to hear the trigger for Midas: it always amazes me how apparently inconsequential events in the world can hit one’s imagination sideways, then suddenly... there’s a “what if” or a “why” that needs answering — and that’s enough to get the brain and fingers moving. It’s the real answer to the age-old question of “Where do you get your ideas?” The truth of it often is that there are no actual “ideas” out there: it’s simply that our brains take an innocent or normal event and (because of the way we’re wired, or the mental state we happen to be in at the time), some internal switch gets thrown that turns it into an idea.

Two other things strike me about what you say. The first is how Midas is part of a body of work coming at death from different angles. It is such a crucial subject, one that shines a light either bright or shadow-inducing on so many parts of the human experience: also an area that I believe “horror” deals with far better and more authentically than any other genre. Instead of ignoring the subject because it’s sad, or using it merely as a plot point or punchline, horror invites the fact of death into the story as a main theme, as another character, letting its deep and important role in our lives out onto the main stage. Midas deals with the subject in such a rich and mature way, too: not as if someone’s saying “Hey, death, right? Jeez, heavy,” but instead with the authority of someone’s who felt and experienced it, and sees how any particular source of grief can affect people in quite different ways.

And secondly, I certainly did notice the sparseness of the language, and that’s part of what makes the book so effective. The bigger the themes, the easier it is to feel you have to editorialize, to lead the witness, to tell the reader what you want them to be thinking at any given moment. Far more effective, as you do in Midas, to present the audience with clarity — both in terms of what’s happening, and the characters’ reaction to it — and let them do the emoting themselves.

I hope you find a mass market home for the book soon, though Paul Miller and Earthling have done a wonderful job with this edition. I’ve been lucky to work with him on several projects, and a few recently with Bill Shafer at Subterranean (who do amazing work, and genuinely care about every single step of the process), one with Cemetery Dance, and with PS Publishing — it’s people and companies like this (and editors like Stephen Jones and Ellen Datlow) that keep the genre going during its periodic down-cycles.

The idea of a novel being “in conversation” with another is fascinating, and I can absolutely see how Midas works that way with Pet Sematary. I don’t think I’ve ever done that, not consciously at least, though I guess with the three Straw Men novels I was doing something similar with the entire “serial killer thriller” genre. Trying to communicate ideas I had about how the phenomenon could be interpreted (at least in some cases) as an extreme example of a capacity for neurotic obsession that is in all of us: in effect taking serial killers off the dark “Nothing to do with the rest of us, they’re just evil and weird...” pedestal which many writers put them on, and seeing them instead as existing at the very far end of a spectrum we all sit upon.

I also wanted to extend the subject out of the psychological into the cultural and historical, to speculate about deep background and perhaps even evolutionary advantage. Just trying to open the doors and windows of the field, I guess. Not sure whether I succeeded, but they were fun to write.

Tyler — thank you for taking the time to talk to me. I’ll end on one last question... what’s next? In terms of publishing schedule, but also about what plans you have, and your hopes for the next few years?

TYLER: That’s a great point about ideas. And who knows what that internal trigger will be, or why? Sometimes it’s as inconsequential as a horse, or something as significant as the death of a loved one. I imagine the inside of a writer’s brain is like a disassembled puzzle, with the final image being unclear until the pieces start coming together to form something meaningful. Even then, where all those pieces came from in the first place is up for debate. Which is to say, the subconscious plays as much a role, if not the most important role, in the process.

I really love the idea of horror dealing with death in an “honest” way and allowing room for it to be present, whether as background or as a character of sorts. I completely agree with that. Horror, more than any other genre, allows loss and grief to take center-stage, and dares to let those emotions almost become monsters themselves. I’ve always found it fascinating how many horror tropes are stand-ins for other things. A vampire could represent cancer, a werewolf could be an alcoholic, a demon could be regret. It allows the genre to tackle heavy subject matter and themes without getting behind a pulpit. I think people are inherently suspicious of anything that sounds like preaching, and horror is typically really good at avoiding that. Not that the monsters need to represent anything—a monster can be just a monster after all—but it does allow the reader to bring their own baggage on the train and take a very specific kind of ride.

Speaking of a reader’s baggage, that ties into what you were saying with “sparseness.” I recently read Willy Vlautin’s excellent novel The Night Always Comes, and the prose is so lean I couldn’t help but fill in all that empty space with my own emotions. And as a result, that book absolutely floored me. That’s not to say the book didn’t do all the heavy lifting, only that it gave me room to participate in it. It didn’t tell me what to feel. It simply presented the unfolding story and allowed me to explore some of my own conflicted thoughts within the pages. Dave Eggers’ novel The Parade does something similar. The spare prose activates the brain in a very different way than something maximalist, something that spells out each and every detail. Which I love just as much, but it’s a different experience.

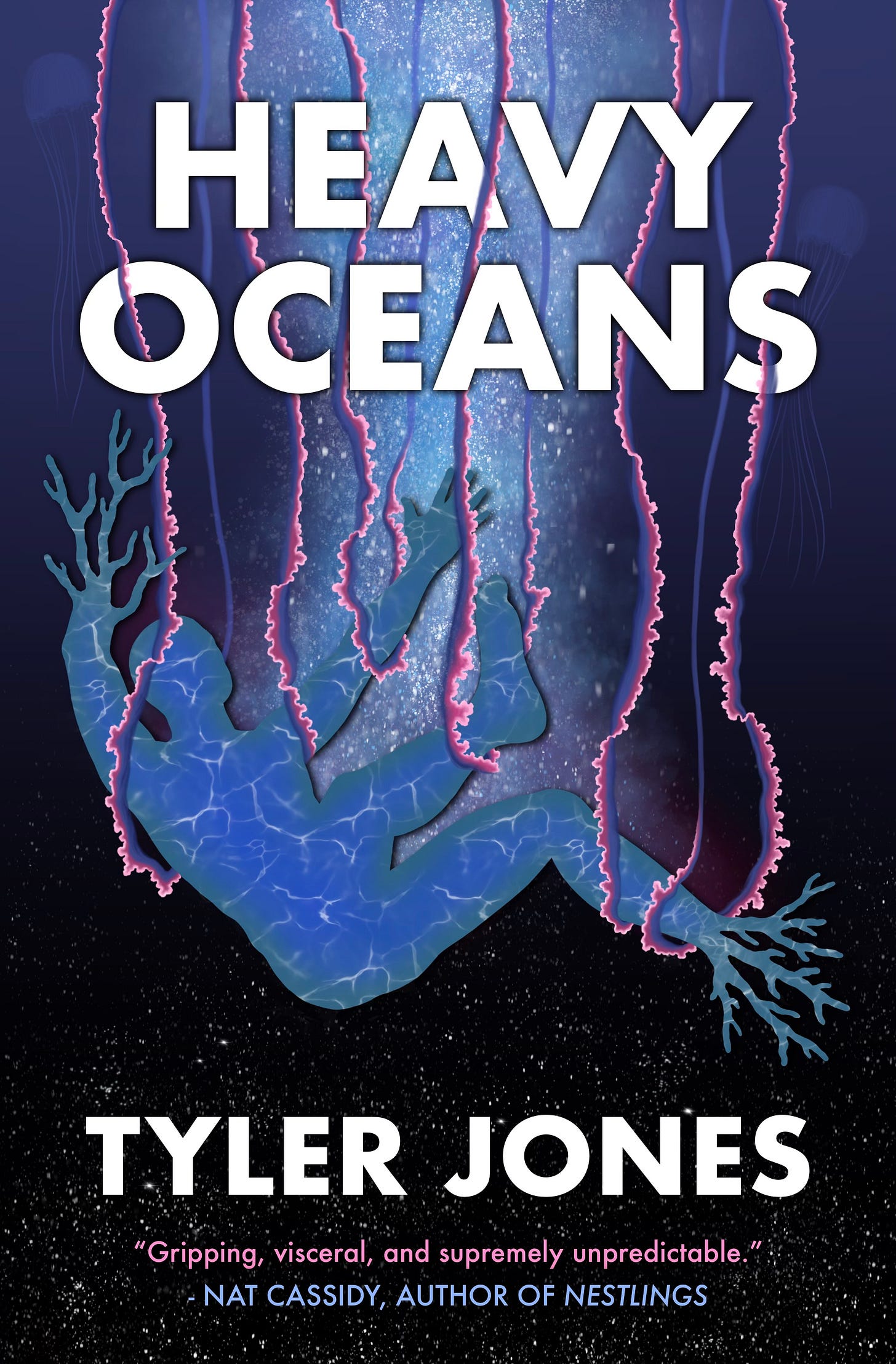

What next? Well, first I have a new short novel coming out through DarkLit Press on December 7th called Heavy Oceans. We’re pitching it as a cross between The Mist and Jordan Peele’s Nope.

It should be available for pre-order within the next couple weeks.

The deluxe edition of Burn the Plans will be published by Thunderstorm Books later this month, with stunning cover art by Ben Baldwin. Then in January, I’ll be publishing a collection of three novellas called Turn Up The Sun, which collects stories from several limited edition books into one volume.

I also have a completed novel called Night of the Long Knives, but I shouldn’t say too much about the plans for that one, yet. And I’m just over halfway through a new novel called Full Fathom Five, which connects and expands on two stories from my collection Burn the Plans into one complete, epic story.

My hope is that Midas, along with these other novels, can find could good publishing homes and readers. As you know, there are so many amazing books being written by amazing writers, it’s almost overwhelming. Knowing how and when to promote your work is complicated on the best of days. So much time can be spent trying to make people aware of your books that it can really eat away at time for writing. So I try and do my best to focus on the work itself, the actual writing, and hope the stories find the right readers. So much of what happens once a book is published is out of our control anyway. What I can control is what happens on the page and make it the best I can at the time.

Michael, thank you for the opportunity to chat with you. It’s been a privilege. One of these days, we’ll have to do it at a pub in sunny California.

damnit, no respect for my teetering TBR pile.

*adds to list*

When I find an author (or musician, actor, director) I like, I definitely go on a spree of consuming all of their work...which raises a question, before I go out and buy all the Tyler Jones I can find: what's the best way for people to buy books, from the standpoint of the author actually making money? Is there a payout difference between Kindle/print from Amazon/in store Barnes & Noble?